This post is part of a living literature review on migration. For more information on the project, see here.

Many, if not most, people think admitting more immigrants leads to higher crime rates. This belief is widespread across the UK, the US, Chile, Belgium, Italy and most likely quite a few other countries. But are immigrants more likely to commit crimes than native-born citizens?

For many decades,1 social scientists across a variety of disciplines - criminology, political science, and economics, to name a few - have tried to understand the relationship between immigration and crime. This post is the first in a series examining what the academic literature has to say about immigration and crime.2

This post will focus on the relationship between immigration3 and crime in the United States, because 1) it is the most studied case, as it is where many academics happen to live, 2) it is where I happen to live, 3) it is very much a live topic of political debate in the US.4 I plan to look at the relationship between immigration and crime in other countries in future posts.5

Note that results in the United States may not generalize elsewhere; different countries have very different immigrant populations and legal systems.

How Do We Study This Question?

There are several common approaches to studying the relationship between immigration and crime:

Examining descriptive statistics

Correlational designs

Difference-in-difference designs

Shift-share designs

Representative census data

The quality of these approaches varies, and I discuss in each section why I put more weight on types of evidence than others.

Descriptive Statistics

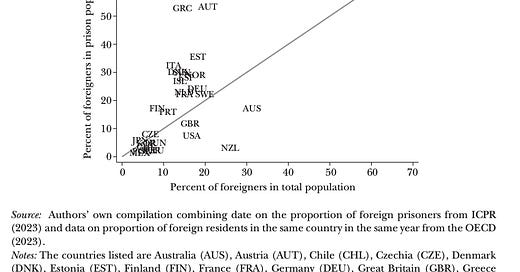

News organizations often plot the percentage of immigrants in prison vs. the percentage of immigrants in the population.

(from Marie and Pinotti 2024, though the FT also has a variant on this chart)

Based on this graph alone, one might conclude admitting more immigrants probably means higher crime rates in Switzerland, but lower crime rates in the US - and perhaps Americans should shut up about immigration and crime.

Unfortunately, we cannot really draw either conclusion from this graph, because the percentage of foreigners in prison can be biased in important ways.

This graph might overestimate the rate of immigrant crime because:

Racial or ethnic bias in the justice system could lead to more convictions for immigrants than the native-born, even if they are committing crimes at the same rate.

The crimes immigrants may have committed could be immigration offenses. In the US, 86% of undocumented people charged with a crime are charged not with a violent or property crime, but with being in the country without permission. The native-born cannot commit immigration offenses in their home country, so mechanically, immigrants commit more immigration offenses than the native born.

I’m also fairly certain this isn’t the kind of crime most people worry about when they worry about immigrants and crime, and thus, a high rate of immigration offenses wouldn’t tell us much about the relationship between immigration and “real” crime.

This graph might underestimate immigrant crime because:

Criminal immigrants are deported and thus don’t appear in the prison statistics.

Immigrants commit crimes against other immigrants. There is evidence suggesting that both documented and undocument immigrants are less likely to report crimes to law enforcement; this might allow criminals who target this population to get away with more.

Correlational Designs

The above graph is basically showing 1) the number of immigrants in a large number of communities, 2) the crime rate in a large number of communities, and measuring the correlation.

However, this graph misses something important in terms of geography - what if places that immigrants settle are systematically different from places where the native-born live? For instance, let’s say 100% of immigrants settle in areas where there is a lot of crime and a lot of police. It is quite likely that people in these areas would be arrested more often than people in areas with less police, even if they commit crimes at the same rate.

If all immigrants were in highly-policed areas, and not all natives were, that might lead one to believe immigrants committed more crime, even if they did not. In order to account for this, the criminology literature begins with a simple correlation, but adds controls for a variety of ways that communities with lots of immigrants might differ from those with few immigrants - e.g. income, level of education, unemployment rate, non-immigrant ethnic breakdown, etc.

Ousey and Kubrin 2018 conducts a meta-analysis of this correlational literature, and finds that increased immigration is associated with a very slightly lower crime rate (but too small to be a real difference).

OK, case closed, immigrants don’t cause crime, right? Not so fast. Studies like these are incredibly sensitive to omitted variable bias - that is, if there is anything that is driving both crime rates and immigration that is not included in the analysis, the result will be wrong.

For instance, new immigrants might choose to go to areas that are inexpensive, because they are moving from a poorer country to a richer one, and don’t have that much money. That area might be inexpensive because crime rates are already starting to rise and therefore, no one wants to live there. Thus, more immigrants are arriving as crime rates increase, but the immigrants are not causing the crime; it’s the other way around. Increased crime is causing immigrants to move to a place, rather than immigrants causing increased crime.

On the other hand, immigrants might choose to go somewhere where there are lots of jobs. In general, if there are lots of high paying jobs available, crime is less attractive. After all, why would you bother robbing someone and risk prison time if you can make a living another way? Fewer people become criminals in these areas, and crime rates could drop. But the drop in crime rates is not because immigrants are moving there, but because of other factors in that area.

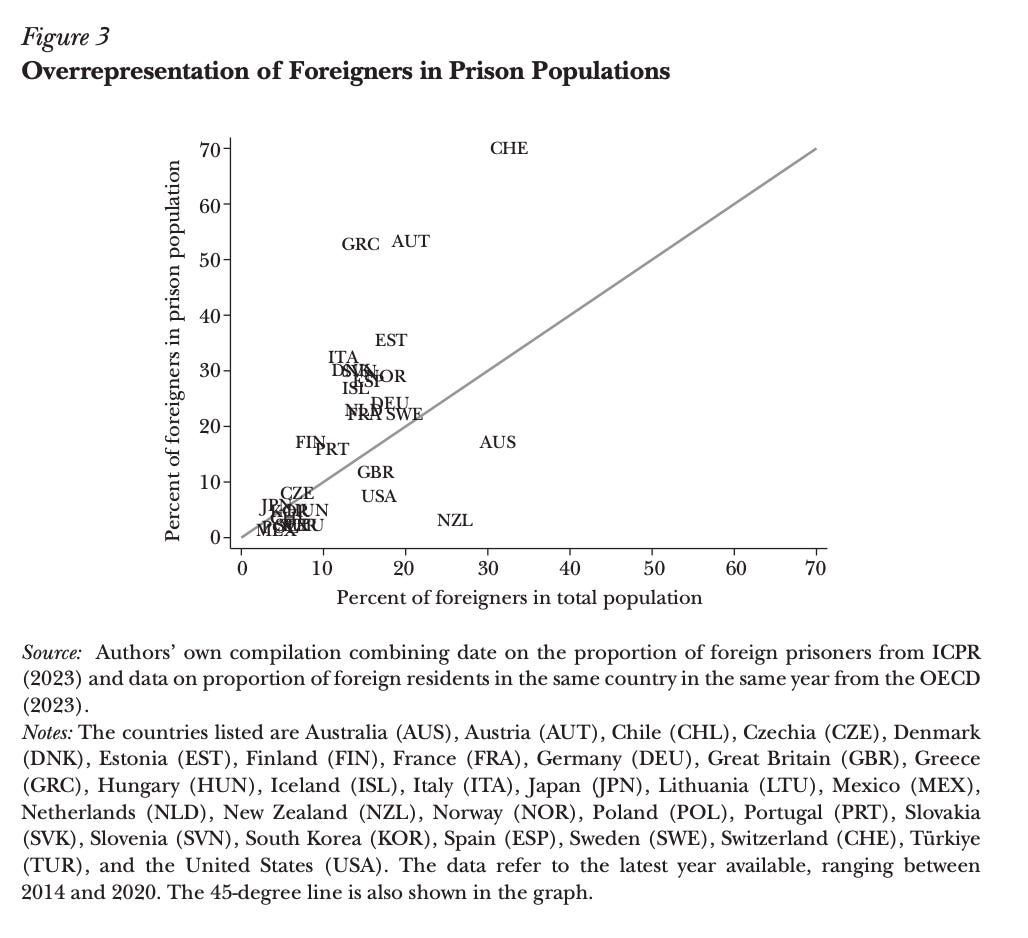

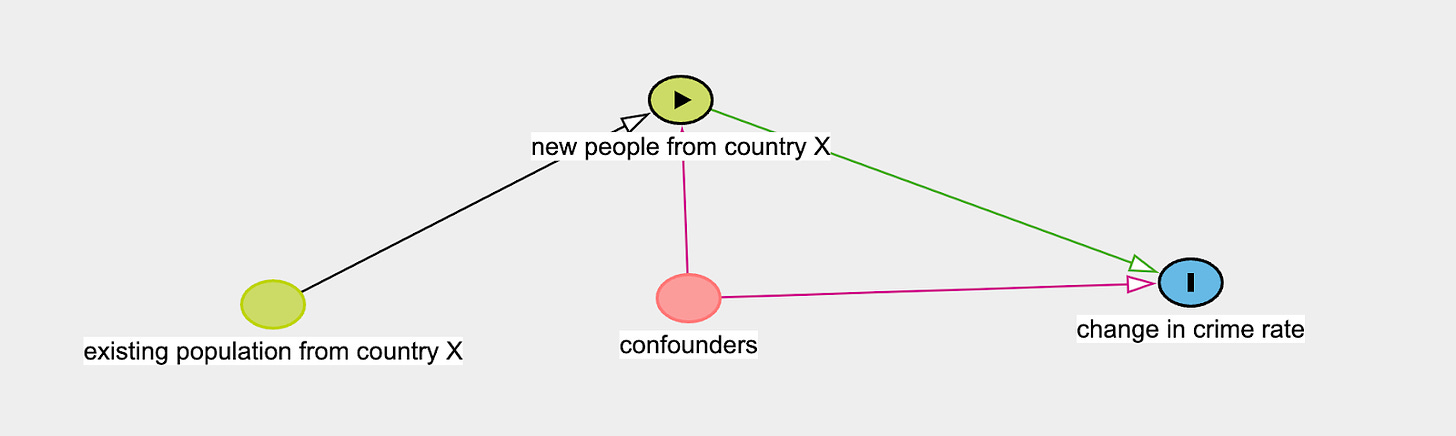

It may be helpful to visualize this as follows. We want to know in a world where the flow of immigrants increases, what happens to the crime rate. This is shown by the green arrow below, the relationship between new immigrants from country X and the change in the crime rate.

But there are many different possible red arrows that are related to both the number of new people from country X and the change in the crime rate. Maybe there’s a crash in housing prices; immigrants move in because it’s cheap and also people on the edge end up turning to crime because the economy’s so bad and they just need to get by.

If we control for all of the possible red arrows, we can correctly estimate the relationship between new people from country X and the change in the crime rate. But if we miss any, our estimate of the relationship between new immigrants and the change in the crime rate could be wrong.

It’s likely that we’re controlling for most of these variables, but it’s possible we’ve missed - or mismeasured - something. We’re probably not completely wrong, but we might be kinda wrong.

Therefore, I think this kind of associational evidence is suggestive that immigration doesn’t increase crime rates - but I wouldn’t call it a slam dunk. Correlation really doesn’t prove causation, and I prefer to look at designs that do try to isolate if immigration causes crime rates to increase.

Difference-in-Difference Designs

Unfortunately, proving causality is hard.6 In most of science, you’d conduct a randomized experiment to determine a causal relationship. For obvious reasons, this is often not possible in social science; Immigrants, as previously noted, are very rarely randomly assigned.

Instead, you must look for a quasi-experimental design, where something is distributed in an as-if random way, or where you can compare two groups that would be otherwise similar. One popular way to do this is with a difference-in-difference design.

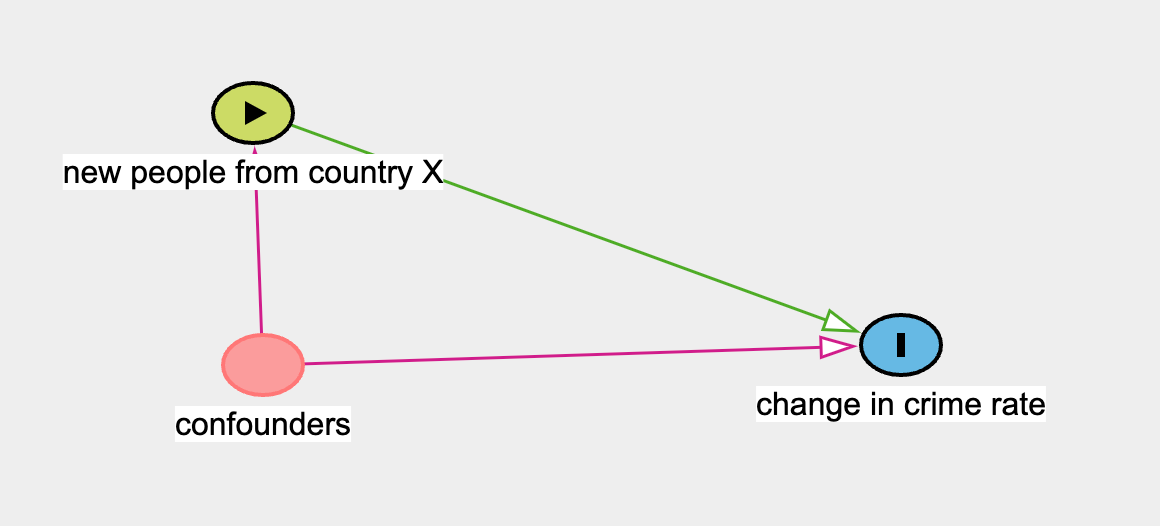

I briefly discussed difference-in-difference designs in my post on the Mariel Boatlift. In this design, you look at how a control group (group S, in the figure below) and a treatment group (group P, in the figure below) evolve over time.

You assume that in the absence of the treatment, they would have evolved in the same way - S1 would have increased to S2, and P1 to Q. This is called the “parallel trends” assumption.

Any changes from the expected outcome, Q, are due to the treatment. Thus, when group P ends up at P2 at time 2 instead of Q, that change was due to the treatment and the treatment effect is P2 - Q.

To use such a design for migration, you need one group (often a county or region) that receives the treatment and one (county or region) that does not, or one that is more exposed to the treatment than the other.

Masterson and Yasenov 2021 looks at Trump’s executive order in January 2017 that halted refugee resettlement. In some counties, immigration rates declined a lot because the refugees who would usually be resettled there didn’t appear. In other counties, this made absolutely no difference to immigration rates, because there weren’t going to be any refugees resettled there anyway.

Was there a difference in how crime rates changed in these counties vs. the counties where there was no change in immigration? Apparently not. Suddenly decreasing the number of refugees resettled in a place did not change crime rates; this paper reports small confidence intervals centered around zero.

This paper, like all difference-in-difference papers, does rely very heavily on the parallel trends assumption - that before 2021, crime trends in counties with high and low populations of refugees were similar and in the absence of refugee ban, they would have continued on similar trends. I was initially very skeptical of this assumption, but the appendix provides reasonable evidence that they were on similar patterns before 2021, so I’m willing to buy this assumption.

Masterson and Yasenov 2021 therefore adds to our weak conclusion from correlation designs that immigration has very little impact on crime rates.

Shift-Share Designs

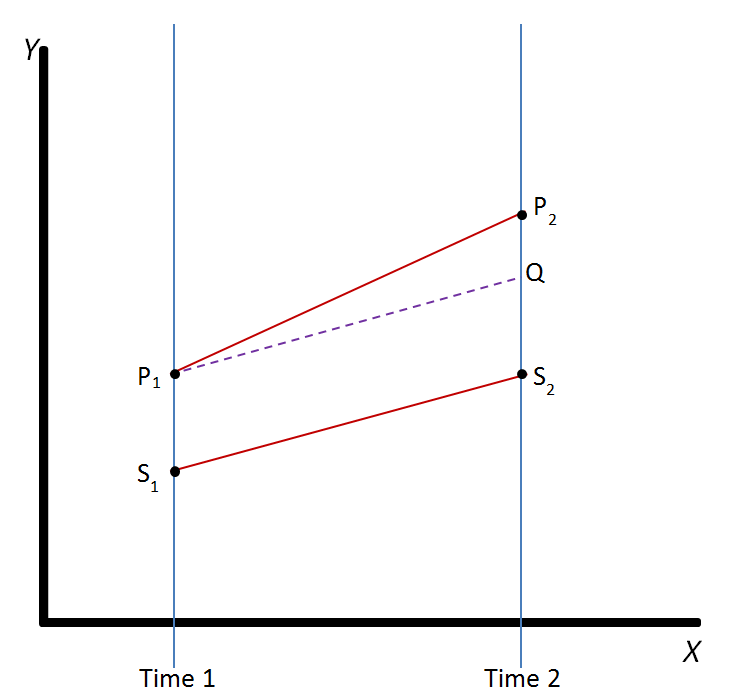

Another popular quasi-experimental design is called a shift-share design. Again, immigrants aren’t randomly assigned; indeed, many immigrants choose to live in areas where there are already other immigrants from their country of origin.7 The shift in the number of immigrants from country X that choose to move to region Y is dependent on the share of immigrants from country X that already live in region Y.

The existing population of immigrants has no impact on how the crime rate will change when these new immigrants arrive - after all, the old immigrants have been there a while; they’re not doing anything new that would suddenly change the crime rate. They do, however, influence how many other immigrants from their country decide to settle in region Y, and that might affect the change in the crime rate.

Shown graphically, it looks like this:

In econ-speak, then, the network between the existing population and the new population is an instrumental variable that drives how many new people settle there.8 In human language, the distribution of the previously existing population of immigrants does end up influencing how the crime rate changes with new immigration - but only through how many new immigrants decide to settle there.

Instrumental variable designs are notoriously hard to get to work. Here, we need the network relationship to: 1) influence how many new people settle in an area, 2) not directly influence the change in crime rate, and 3) not be related to any other reasons that the crime rate might change.

I’ll discuss the plausibility of these assumptions in a minute, but for the moment, it suffices to know this is a popular way to study changes due to migration. There are several US immigration-and-crime papers that use this design: Chalfin 2015, Spenkuch 2014, and Amuedo-Dorantes, Bansak and Pozo 2020.

Chalfin 2015 uses a slight variation on this design9 to study if increased immigration from Mexico increased crime rates. He finds an increase in the rate of assaults when there are more immigrants from Mexico, but a decrease in the rate of rape, larceny, and motor vehicle theft. The effects are relatively large; he finds that the increase in immigration from Mexico from 1990 to 2000 may have been responsible for up to half of the decrease in the national rate of property crimes during that period.

Note that doesn’t mean the total number of property crimes decreased because there were a lot of Mexican immigrants in the 90s. It does mean that, for instance, if you lived in a neighborhood with many recent immigrant Mexican-Americans, you would be less likely to experience a property crime, because the people around you would be less likely to rob you than other groups.

Spenkuch 2014 finds exactly the opposite result - immigration had no effect on the rate of violent crime, but that immigration between 1980 and 2000 increased the rate of property crime. He finds that “immigrants commit circa 2.5 times as many [property] crimes as the average native”, and that this result is driven by immigrants from Mexico.

Lastly, Amuedo-Dorantes, Bansak and Pozo 2021 uses a shift-share instrument for refugee resettlement. This paper finds no statistically significant relationship between refugee resettlement and crime rates between 2006 and 2014.

Taking these papers as a whole, they are somewhat inconclusive about the effects of immigration on crime rates in the US. All three find no impact on most types of violent crime; ⅔ find no impact on assaults. But who knows about property crime - perhaps Mexican immigrants are much less likely to commit property crimes than the native-born (Chalfin), but perhaps they are much more likely to do so (Spenkuch).

There is also a catch to the interpretation of these papers. As I noted above, shift-share designs rely on a number of assumptions, and there are reasons to believe those assumptions might not actually hold here.

There are two major lines of concern about using shift-share designs to study migration:

Jaeger, Ruist and Stuhler 2017 argues that shift-share designs are not valid when one considers labor market adjustments to immigration. When immigrants enter a labor market, there could be a short-term loss of jobs (because immigrants get hired instead of native workers) but a long-term increase in jobs (because there are now more consumers that need goods and services). A shift-share design doesn’t distinguish between the short- and long-run responses to immigration inflows, and thus, you get some kind of weird average across those.

I’m somewhat less concerned about different short-run and long-run responses in crime rates than I would be for labor market responses, because I expect the long-run and short-run responses to be the same. Whatever effect immigration has on crime rates, we expect to have the same sign over time; we don’t have a strong reason to think it might briefly increase crime rates and then decrease them again.10

For a shift-share design to be valid, the initial placement of settlers must only be related to any current changes in crime rate because the initial placement influences later settlement patterns.

Borusyak, Hull and Jaravel 2024 and Terry et al 2022 both discuss reasons that this might not be true. The reasons that drove initial settlement could still be driving crime today. If that’s true, shift-share designs can’t be used.

Chalfin attempts to deal with this possibility by incorporating random variation in cohort size in his network instrument. The other two papers do not, though, and I don’t really have a good way to adjudicate if the reasons people initially settled in a place are still important.

Thus, I consider those two papers largely suggestive but not conclusive as well. Of these papers, I put most weight on the result from Chalfin - that immigration reduces the rate of most crimes, but possibly not all.

Representative Census Data

There’s one last (and relatively recent) methodological innovation that one can use to examine the relationship between immigration and crime. Instead of just looking at a snapshot of how many immigrants are in prison at a given time, one can consider the entire universe of crime-related outcomes of the universe of native-born residents and immigrants in the United States.

Abramitzky, Boustan, Jácome, Pérez and Torres 2024 assembles the first nationally representative series of incarceration rates for immigrants and the US-born between 1870 and the present day. This fixes two important flaws in simple correlational graphs like the one we started with:

Census data allows you to see if immigrants are not in prison but still in the US, or if they’ve been deported.

They distinguish between immigration offenses and other types of crime.

Still, they find that immigrants have been less likely to be incarcerated than the native-born since 1880, and significantly so since 1960. By the present day, an immigrant in the US is about 50% less likely to be incarcerated than a native-born American.

Immigrants of all sending regions are less likely to be incarcerated than Americans, including Mexicans and Central Americans. This is not simply because the US has admitted immigrants with characteristics that would make it less likely that they would be involved in crime than the US-born (e.g. more education, older age, etc). Immigrants with low levels of education are significantly less likely to commit crimes than the US-born with similarly low levels of education.

I should note: no matter how impressive the data work here is - and it’s very impressive - it does not fix all the flaws of correlational data. If the justice system is biased, or crimes aren’t reported, this kind of design can’t fix that. All the information we have is what the justice system has recorded, with little way to correct for that.

In this case, I’m not too concerned about the bias of the justice system resulting in spurious conclusions. For the result they report to be incorrect, the justice system would have to be biased in the favor of immigrants. The authors (and I) think this is unlikely; they cite Light, Robey, and Kim 2023, Goncalves and Mello 2021 and Tuttle 2023 that the opposite is likely true.11

They also think it is unlikely that immigrants are less likely to be charged with a crime simply because their (sometimes undocumented) victims don’t report crimes as often out of fear of police. They show that immigrants were less likely to be incarcerated for decades prior to the rise in deportations (at times when undocumented immigrants were less frightened to interact with the justice system). Perhaps it is still possible that all the migrant criminals are committing crimes against other migrants, since even documented migrants are less likely to report crimes to police. In theory, this could drive the result that immigrants are less likely to commit crimes than natives.

I don’t think so, though. Considering the size of the incarceration gap between immigrants and non-immigrants, it seems most likely that American immigrants really do just commit fewer crimes than natives - and have done so for many decades.

Conclusion

When we look across a wide variety of research designs, there is very little evidence that immigrants in the US commit more crime than the native-born. Of the papers we examine, there is only one specification that shows an increase in crime rates (assaults in Chalfin).

There is some evidence that immigrants have no impact on crime rates (Masterson and Yasenov), and some evidence that immigrants are much less likely to commit crimes than the native born (the other outcome variables in Chalfin; Abramitzky, Boustan, Jácome, Pérez and Torres).

Taking all of this together, it seems most likely that immigration has a zero-to-negative impact on crime rates in the US. Put another way, Donald Trump is exactly wrong to worry about an influx of criminal migrants; based on past patterns, admitting more immigrants into the United States is more likely than not to decrease crime rates.

Thank you to Denise Melchin, Andrew Miller, Emma McAleavy, dynomight, Oliver Kim, and Alex Manning for their comments on drafts of this post; thank you to Daniel Millimet and Peter Hull for econometrics help. Any remaining mistakes in explaining econometrics are my own.

People have also been worrying about this for a while; the earliest paper I found on it was from 1896. (There’s also a nice bit in this paper about how you simply cannot compare populations with different age structures, proving we’ve been having the same discussions about statistics for 128 years.)

Note that no posts in this series will attempt to give policy recommendations. A living literature review reviews the literature and what we currently know on a subject; what policy makes sense given that information is beyond the scope of a literature review.

This post focuses on immigration writ large, and looks at overall immigrant flows. This means it largely focused on documented immigrants, as ~80% of US immigrants are documented. A future post will focus on the effects of undocumented immigration specifically.

The profile of the issue has been recently raised by President-elect Donald Trump’s insistence that the US is full of criminal migrants who have caused a surge in crime.

It may not be the next post, though, because my next post is supposed to go up on Christmas Eve and even I am likely to balk at sending out 3000 words on crime on Christmas Eve.

I have taken - and TAed - multiple classes on causal inference. I still regularly tweet complaints about the fundamental problem of causal inference.

For instance, for reasons of shared language.

You can also get an exogenous instrument if the shifts are exogenous, rather than the shares; you can see more on that in Borusyak, Hull and Jaravel 2024. However, we’ve already discussed that migration choices are rarely exogenous, so I don’t discuss that case here.

If previous migrants were drawn to a city for reasons related to the current crime rate, the instrument wouldn’t be valid. He based his network instrument on random variation in the cohort size instead; if there are more Mexicans born in a particular year, more of them are available to migrate.

Most people that commit crimes tend to keep committing them.

This will come up again when I discuss crime and immigration in Germany in a future post. There, as the correlation graph shows, immigrants are overrepresented in prisons. However, there I am concerned that this could be (at least partially) driven by unequal enforcement and discrimination.

>In this case, I’m not too concerned about the bias of the justice system resulting in spurious conclusions. For the result they report to be incorrect, the justice system would have to be biased in the favor of immigrants. The authors (and I) think this is unlikely; they cite Light, Robey, and Kim 2023, Goncalves and Mello 2021 and Tuttle 2023 that the opposite is likely true.

This ignores the existence of concerted lobbying activity by NGO and activist groups, the pro-bono support offered by the legal profession, the phenomena of judicial activism, activist pressure placed upon civil servants and law enforcement (even setting aside the question of institutional capture), and casting a critical eye over the biases of social scientists (especially pertinent in the context of the broader crises of methodology and replication).

One setting that seems ideal to study this question is Switzerland's random assignment of refugees to cantons (studied here https://drive.google.com/file/d/1b9sQ_h53t648PTA-CmGIH9gpwq7oP40f/view?usp=sharing). This paper doesn't do it and I don't know if any other papers use the same setting. Though there would be external validity concerns (from the first cross country correlation graph, Switzerland is probably an outlier in the immigration-crime relationship, and refugees are not typical voluntary migrants)